Source:

McDermott, R. (2023, June)). On the scientific study of small samples: Challenges confronting quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Leadership Quarterly 23, 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2023.101675

Full text here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1048984323000012?via%3Dihub

The gist:

On research vs science as a general introduction: McDermott writes from a positivist perspective, but she is very careful in her opening discussion to define what she sees as the difference between “research” and “science” in a way that doesn’t bash qualitative or interpretivist researchers. (I don’t fully agree with her opening discussion, but I definitely appreciate it.) She critiques poor research design on the part of both quant and qual researchers, and delivers well-deserved criticism of interpretivist researchers attempting to use qual methods to establish causation. (I’m not sure how often this happens in interpretivist research, but the pressure to “prove something” through one’s work is immense.)

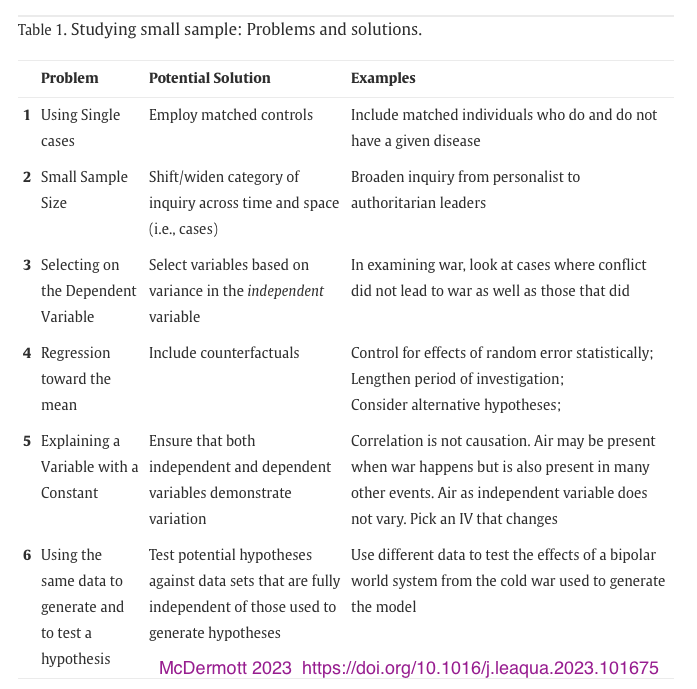

On avoiding key research errors when working with small sample sizes: This is where the article really shines. McDermott reviews 6 key problems and offers a solution for each. The summary of her suggestions appears in this screenshot of Table 1 (the entire article is online for free), but I encourage you to read the discussion, as she provides many helpful examples to illustrate both the problems and the solutions.

My thoughts on McDermott’s discussion

I don’t agree with every point here; as a qualitative researcher, I find single-case research to hold value even if it does not fit McDermott’s definition of “scientific,” and her recommendation to add cases to avoid a single-case study doesn’t fly in many real-world settings (like examining a particular unique and non-reproducible instance of failure or success).

That nit-pick aside, I took to heart many of her critiques.

For example, it is tempting as a qualitative researcher to use the same data to both generate a theory / hypothesis as well as draw a conclusion about that statement using the same limited set of data. However, more robust research would use an initial study to identify key ideas and themes for future follow-up research, building study upon study. Of course, funding is the bugaboo here; we can do only what we can afford to invest of time and resources, and those are finite (even if the money is available, which it often is not, especially for non-quantitative approaches). But interviewing over Zoom costs only time and effort and outreach. An investment, yes, but one that could pay off with a much more valuable dataset and more established conclusions.

One of McDermott’s primary suggestions is to seek opportunities to find counter-factual observations. This advice lines up with a central theme that arose out of my reading in constructivist grounded theorists like Kathy Charmaz, whose 2014 handbook for grounded theory continually emphasized the need to go beyond simplistic explanations and to seek out participants whose experiences or contributions would challenge the emergent theory. The author’s examples drawn from historical research where particularly useful here, such as her critique of some classic leadership studies which made assumptions about leadership causes and effects too hastily.

One example of bad research that I’d not read before: the famous “queen bee” study that proposed powerful women inhibit the growth and development of younger, less established women in their orbit to stifle competition for their power, was written on only one set of data, with no counterfactual investigation. Later research refuted the whole idea! I’ve heard that “queen bee” research cited many times; it’s probably passed into head canon for many folks who read HBR and track equity issues in management. Launching a splashy article on a single dataset is suspect, always, but current publishing pressures push “new” research over the crucial work of verification and replication of proposed ideas.

Readability & Value

I found this article to be highly readable, accessible, and clear. I would expect any graduate student to be able to read these few pages (the PDF is only 10 pages) and follow McDermott’s article and recommendations. Upper level undergraduate students should be able to work through the article with scaffolding from their professor as needed to provide context on the issues being discussed. (I would particularly like to see more of this discussion for undergraduate psych programs.)

I would include this as required reading in any graduate course on research methods, whether quant or qual, because she discusses both methodological traditions and offers a working definition of positivist “scientific” research in the opening discussion. She also overviews key techniques for improving any study design. I’d love for this article to be one that doctoral students discuss with their advisors when they are planning their methods section.

Interpretivist scholars may bristle at being excluded from the “scientific wing” of “research,” but we should be used to this by now. And I’m not mad about it; qualitative has more to offer when it’s doing something quant methods cannot do.